Seth Siegelaub’s simple dictum “You don’t need a gallery to show ideas” remains the intellectual, creative, and logistical underpinning of much conceptual, immaterial, and publication-based art practice. Though specifically in reference to non-object based art, what has always struck me about this statement is the sheer freedom, perseverance and optimism it allows and accounts for. This notion may be particularly resonant in an art world increasingly divided along class lines – even more so than when Siegelaub started to engage the economic politics of art in the late 1960s – and at a time when the resources available to artists are scarce, requiring all of us to develop new means of collaboration, production and dissemination.

I’ve always been drawn to conceptual art and artists’ publications, but was not as familiar with Siegelaub’s role in that history until I read Alexander Alberro’s book Conceptual Art and the Politics of Publicity (MIT Press, 2003), focusing on that very topic. At the time, I had recently moved back to New York from Philadelphia, where I had had a small gallery and bookstore, and was struggling in opening a new space replicating the model. Learning of his work, and the new directions he continuously forged as older models failed was truly inspirational, and played a large role in my shift towards being able to curate without a gallery as an anchor or crutch.

Along with the artists he collaborated with, Siegelaub presented a model by which artists and curators could produce and circulate their work on their own terms, and in a way that was designed to make use of any conditions given. Most notable for his promotion of conceptual art, and a stark refusal of the traditional gallery system, he was the first curator and dealer of conceptual art in the US to focus on works that did not necessitate a physical gallery space. His trajectory however began with a gallery, Seth Siegelaub Contemporary Art, located at 16 West 56th St., in what remains the relatively traditional and higher brow midtown gallery neighborhood in New York. From the outset he attempted to show – and sell – extreme performance oriented installations and other works generally unappealing to collectors. The gallery closed in 1966 after less than two years of operation as sales failed to cover overhead. Shortly afterwards Siegelaub took to dealing and hosting salons out of his apartment, and expanded even further his already bold promotional efforts of each project.

“Douglas Huebler: November 1968,” was the first exhibition organized by Siegelaub in which the catalog was the entire show. In a shift away from the artist’s previous work in minimalist sculpture, Huebler had re-oriented the notion of “site” in his work to documentation of travel and placement. Serendipitously, this departure from the necessity for a physical exhibition space to communicate the work coincided with Siegelaub no longer having a gallery, and an inability to find funding for sculptural pieces. As a result, an alternate means of exhibition and dissemination was invented that would allow for a new level of artistic and curatorial autonomy, and pose a challenge to the standards of what was accepted within the art market.

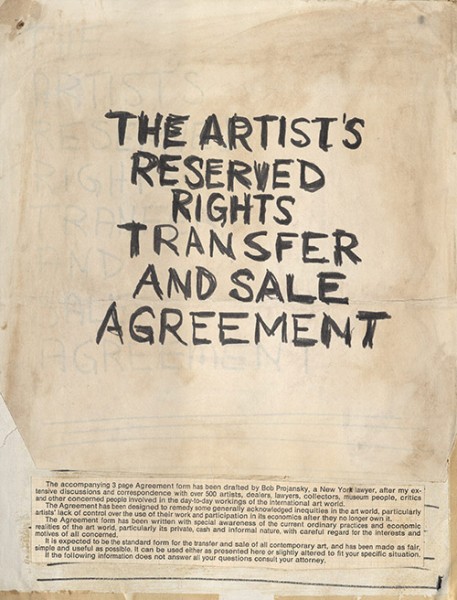

Alongside curatorial work Siegelaub became involved in the major art activist group the Art Workers Coalition (AWC), whose platform issues included fighting for artists to be recognized and remunerated as legitimate workers, to have a greater say over the context in which their work was presented, and for institutions to improve racial and gender based inequities in the art world. While not a steering member of the coalition, Siegelaub’s efforts included a statement during the group’s seminal Open Hearing at the School of Visual Arts, in which he stated “… it would seem that the art is the one thing that you have and the artist always has and which picks you out from anyone else… This is the way your leverage lies.” Here Siegelaub asserts three things: that one’s art-production is to be valued as any other form and product of labor; that artists can instrumentalize their work in efforts for social, economic and political change; and that the goals artists strive for in their professional and creative lives are intertwined with their simultaneous positions as citizens and workers. This notion of activating one’s art as a political and economic tool culminated in Siegelaub’s collaboration with lawyer Bob Projansky to create The Artist’s Reserved Rights and Transfer of Sale Agreement in 1971, which enabled artists’ to assert re-sale rights, control over reproductions of their work, and exhibition context, among other terms.

My friendship with Siegelaub was relatively brief, not much more than a year, and we were only in the same locale for three months of that. I reached out to him in the summer of 2011 to let him know I would be in Amsterdam that fall, and to ask if I could help with any of his many projects. I soon began conducting research for him and working on his website from New York (the unfortunately defunct egressfoundation.net), which continued into my time in The Netherlands. Unlike many others I have worked for in the arts, Siegelaub insisted that I be paid for my time, bringing it up even before I did – a sign of respect for one’s labor and time that can be hard to come by when working as an artist or administrator. The values in favor of economic justice for artists and art workers that Siegelaub promoted in his art and publishing efforts were mirrored in his actions in the world.

The first time we met we spent the first hour sitting on the roof (odd for an Amsterdam canal house) eating pretzels and drinking very small glasses of wine, and mostly talking about how terrible New York is, how convoluted the art market is, what I’ve been up to, what he’s been up to, and the importance of doing lots of different things in one’s life. At dinner I actually found a fly in my soup, which was hilarious. He was a long talker, sharp joker, full of rants and stories and clearly incredibly committed to the political and economic positions he took. He was also very kind, welcoming, and always interested in sharing ideas and stories.

At the time of his death Siegelaub was in the midst of numerous projects, including his impressive catalogue of historic textiles, his ongoing questioning of how art history is made, and research on international art law, among others. While these efforts may remain unfinished for the time being, the legacy of his work is hugely alive and growing. Investigations into the practical and conceptual meeting of art, law and economics started by Siegelaub are carried on by artist activist groups like Working Artists in the Greater Economy (W.A.G.E.), politically leaning artist-driven publishing efforts like Half Letter Press, and the critical discourse of the Art & Law Program. Artists and curators now regularly employ publishing as a means of communication, dissemination and exhibition of their work, which the popularity and abundance of artist book fairs easily attests to.

In shifting his activity to adapt and react to the inequities of the art world, Siegelaub put forth a premise designed to be expanded upon, presenting an alternative system of values and terms for working in and producing art. We’d be wise to follow that lead.